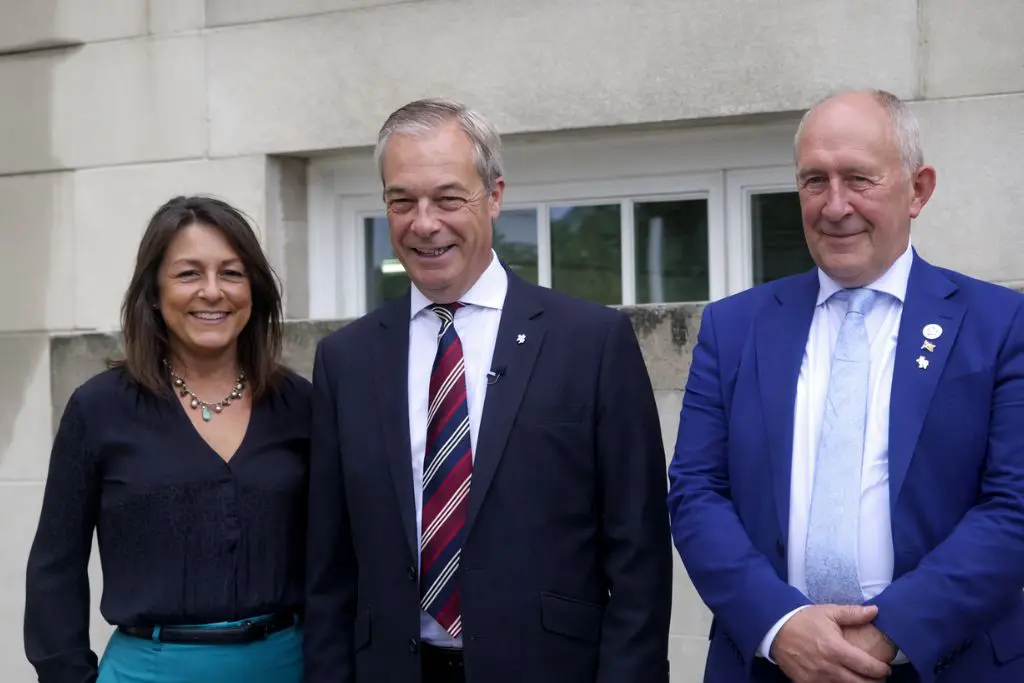

Kent County Council’s new Reform UK leader, Linden Kemkaran, has urged the county’s district councils to take legal action against hotels housing asylum seekers without proper planning permission. The unprecedented move follows a landmark High Court ruling in Essex that has emboldened councils across the UK.

The ruling, which granted a council an interim injunction to stop the use of a hotel for asylum seekers, has sent a clear message. It asserts that local planning law can be used as a powerful tool to challenge the government’s controversial policy.

Kemkaran’s declaration signals a new, more confrontational approach from Kent’s local government. This shift comes as Reform UK takes control of the county council.

The leader has explicitly stated she will be writing to her counterparts in Kent’s district councils. She’ll urge them to check the planning status of all asylum hotels in their areas and to take legal action where breaches are found.

The Legal Basis and a Crucial Precedent

The Material Change of Use

At the heart of this legal challenge is the concept of “material change of use.” In the recent High Court case, Epping Forest District Council successfully argued that converting a hotel for long-term asylum seeker accommodation was a fundamental change from its original purpose. Therefore, it required formal planning permission.

Mr Justice Eyre, the presiding judge, agreed with the council’s argument. He noted that the hotel’s new use had “side-stepped the public scrutiny and explanation which would otherwise have taken place.” This, he added, had contributed to community tension.

This ruling provides a significant precedent. It is one that councils in Kent and across the country are now looking to exploit. The decision has already sparked national debate.

The Government’s Response

The Home Office, which has a legal duty to house destitute asylum seekers, has warned that the ruling could “substantially impact” its ability to provide accommodation nationwide. Government officials were reportedly left reeling by the decision. They fear it threatens to undermine their strategy for housing the thousands of people currently in the asylum system.

A spokesperson for the Home Office maintained that the use of hotels is a temporary measure. It is a necessary contingency to meet its statutory obligations in the face of a high volume of arrivals and a growing backlog of asylum applications.

However, critics argue that what was meant to be a “temporary” solution has become a default policy. A policy that is both costly to taxpayers and disruptive to local communities. The government has pledged to end the use of hotels by the end of the current parliament, but many, including the Refugee Council, argue this timeline is far too slow and unviable.

Pressure on Kent’s Districts

Linden Kemkaran’s call places immediate pressure on Kent’s district councils. Many of them are already grappling with the local impact of asylum hotels. The county, being on the front line of Channel crossings, has a significant number of hotels in use for this purpose.

The situation has created a palpable sense of grievance among some residents and business owners. They point to the loss of tourist accommodation, the strain on local services such as GPs and schools, and a perceived breakdown of community cohesion.

Kemkaran’s directive effectively empowers these local concerns. It gives them a formal political and legal channel through which to be addressed. It also forces district councils to take a definitive stance: either they follow KCC’s lead and explore legal action, or they risk being seen as failing to protect local interests.

Some councils may be hesitant to act. They might cite the Home Office’s legal obligation and the potential for costly, protracted legal battles. They may also face internal divisions. Some councillors may argue that providing accommodation is a humanitarian necessity, while others prioritise the enforcement of local planning laws.

The legal action taken by Epping Forest Council also cited concerns for the asylum seekers themselves. The sustained protests and community disturbance had created a harmful and socially isolating environment. This highlights the complex and multi-faceted nature of the issue. Legal, political, and humanitarian concerns are all intertwined.

The legal challenge is not just about planning law. It’s also about a system that many feel is broken. It places immense strain on both local communities and the vulnerable individuals it is meant to support.

A National Issue

This issue extends far beyond Kent’s borders. The High Court ruling has acted as a catalyst for other councils across England. Leaders of Labour-run councils in Wirral and Tamworth have also stated they are reviewing their legal options. This indicates that the use of planning law to challenge asylum hotels is becoming a cross-party issue.

Reform UK, which has a significant presence in several local authorities, has vowed to pursue similar cases in all the areas it controls. This effectively nationalises what was once a localised dispute.

The Government’s Dilemma

The government faces a significant dilemma. If more councils succeed in their legal challenges, the Home Office could be forced to rapidly find alternative accommodation for thousands of people.

Current alternatives, such as military barracks and other large-scale sites, are already at or near capacity. They have also been the subject of their own controversies. The government’s promise to phase out hotels by the end of the current parliament now looks increasingly difficult to achieve. It may be forced to accelerate its plans or face a potential crisis in housing provision.

Meanwhile, the debate continues to intensify. On one side are those who argue for strict enforcement of the law, highlighting the importance of local democracy. On the other side are those who, while not necessarily in favour of the hotels, argue that the immediate humanitarian need to house people seeking safety must take precedence.

The High Court’s ruling, which placed a “particular importance” on the enforcement of planning control, appears to have tipped the balance in favour of the former. For now, the focus shifts to Kent’s district councils. They will have to carefully weigh the political, legal, and social implications of taking action.

Linden Kemkaran’s challenge is not just to the districts. It is to the government itself. It forces the issue of asylum accommodation out of the realm of abstract policy and into the concrete world of local planning enforcement. The coming months will show whether Kent’s councils embrace this new legal precedent or choose to navigate a more cautious path.